A Brief History

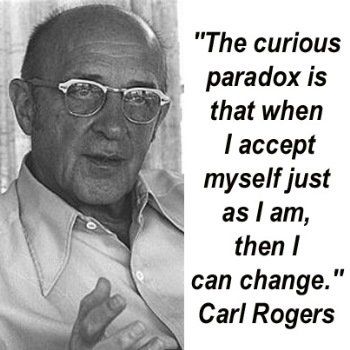

By the early 20th century, play had been identified as an essential means of individual expression for children. With the exception of a few researcher-practitioners such as psychologists, Hermine Hug-Hellmuth, David Levy, Anna Freud, Melanie Klein (1955) and Carl Rogers most psychologists providing treatment to children in the first half of the last century, attempted to utilize therapeutic interventions developed exclusively for adults. The aforementioned innovatory psychologists recognized that play was an ideal medium to allow children’s expression of feelings and underlying emotionality because developmentally, few children had achieved the cognitive or language levels to express such feelings with the use of words. It was Virginia Axline (1947), author of Play Therapy and Dibs in Search of Self and doctoral student of Carl Rogers who “probably did more than anyone else to bring ‘play therapy’ to the attention of the general public interested in psychology” (Kirschebaum, 1979; pg 82).

Like Rogers, Axline emphasized the attitudes and personal characteristics of the therapist and the quality of the relationship between client and therapist as the essential factors in promoting change. Known as nondirective counselling or child centred play therapy, Axline’s therapeutic model paralleled Roger’s theoretical orientation inasmuch as “a core theme in his theory (was) the necessity for nonjudgmental listening and acceptance if clients (were) to change” (Corey, 1991; pg. 204, my brackets). According to Axline, child centered play therapy focused on the child, not on the child’s presenting problem. Like Rogers before her, she promoted a therapeutic relationship based on genuineness, authenticity, unconditional positive regard, acceptance and empathic understanding of the client in order to support psychological development and growth. While a quiet, private space with carefully chosen toys and art materials was provided to her young clients, no special techniques were implemented in the play therapy room and the therapist was cautioned not to probe, direct or make suggestions to the child. Axline wrote, “Non-directive counselling is really more than a technique. It is a basic philosophy of human capacities, which stresses the ability within the individual to be self-directive” (Axline, 1947; pg. 26).

Axline identified 8 basic principles to guide child centered therapists (1947; pg. 73-74, Axline’s italics).

- The therapist must develop a warm, friendly relationship with the child, in which good rapport is established as soon as possible.

- The therapist must accept the child exactly as he is.

- The therapist establishes a feeling of permissiveness in the relationship so that the child feels free to express his feelings completely.

- The therapist is alert to recognize the feelings the child is expressing and reflects those feelings back to him in such a manner that he gains insight into his behaviour.

- The therapist maintains a deep respect for the child’s ability to solve his own problems if given an opportunity to do so. The responsibility to make choices and to institute change is the child’s.

- The therapist does not attempt to direct the child’s actions or conversation in any manner. The child leads the way; the therapist follows.

- The therapist does not attempt to hurry the therapy along. It is a gradual process and is recognized as such by the therapist.

- The therapist establishes only those limitations that are necessary to anchor the therapy to the world of reality and to make to the child aware of his responsibility in the relationship.

In 1988, contemporary play therapist, psychologist, prolific researcher and professor, Garry Landreth, established the National Center for play Therapy at the University of North Texas. An ardent supporter of the child centered play therapy paradigm, Dr. Landreth wrote, “A therapeutic working relationship with children is best established through play, and the relationship is crucial to the activity we refer to as therapy. Play provides a means through which conflicts can be resolved and feelings can be communicated” (1991, pg. 11).

In his book, “Play Therapy: the art of the relationship”, Landreth conveys a deep and abiding respect for children and their innate potential for growth and change on their own terms. Through a unique relationship that genuinely prizes a child’s capacity to self-actualize, he refers to therapeutic objectives in general terms rather than setting specific goals in play therapy. According to Landreth (1991; pg. 80), “the objectives of child centered play therapy are to help the child:

- Develop a more positive self-concept.

- Assume greater self-responsibility.

- Become more self-directing.

- Become more self-accepting.

- Become more self-reliant.

- Engage in self-determined decision making.

- Experience a feeling of control.

- Become sensitive to the process of coping.

- Develop an internal source of evaluation and,

- Become more trusting of self.”